If it is fashionable today to minimize the importance of the knowledge of the particular circumstances of time and place, this is closely connected with the smaller importance which is now attached to change as such.

—F.A. Hayek, from “The Use of Knowledge in Society”

Way too often, conversations about change—whether political, social, organizational (or even personal)—begin with a demand or a Big Plan.

Some authority leaps directly to what he thinks should be done within some preconceived solution set, without first understanding the unique perspectives of those he seeks to engage.

But the key to durable, prosocial change is first to meet people where they are.

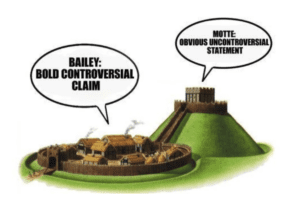

The One True Way Fallacy

Sweeping demands or grand plans too often assume that everyone starts from the same place, faces the same challenges, or has the same interests. For example, a boss demanding that all employees work longer hours—or a government demanding that all citizens work fewer hours—assumes they’re equally productive or have similar responsibilities at home.

But circumstances vary.

Adopting a national policy on x almost always assumes away regional or local variation. For example, a national minimum wage—a uniform price floor on labor—would have very different effects in Mississippi compared with Manhattan.

When we operate from a one-size-fits-all mindset, we inadvertently alienate those who find themselves in different circumstances. And we forget that there is more than one way to solve a problem or carry out a mission.

Monomania is rooted in fallacy: There is no One True Way.

Empathy and Pluralism

Empathy is a cornerstone of understanding. It doesn’t mean always agreeing with someone else’s position, but it starts with trying to understand it. This can be achieved by asking open-ended questions and active listening. By taking the time to understand individuals’ needs and perspectives, we are better equipped to find subtler, more bespoke solutions.

In The Decentralist, I suggest empathy makes pluralism possible:

[Normative Pluralism] is about acknowledging our differences, accepting them, and unleashing the creative forces that arise in the overlaps. Becoming a practitioner of pluralism does not come easily, and it starts with good old-fashioned toleration. In mastery, though, the practice means holding multiple values and perspectives in cognitive and affective juxtaposition. That takes discipline. So many of our reflexive responses work at odds with pluralism. It’s rarely easy to understand and empathize with points of view that might go against the grain.

But therein lies a greater truth.

The more we try to understand and empathize with real people in real contexts, the more we can fashion adaptive strategies to create value together in collaboration.

Tailored Solutions, Local Knowledge

When we meet people where they are, we see how it can be possible to tailor our solutions to fit the unique challenges they face. The political economist F.A. Hayek emphasized the importance of local knowledge, that which is gained in “the particular circumstances of time and place,” which is sometimes more important than scientific knowledge.

When we start to think about solutions, it’s vital to consider local knowledge, which will differ from one context to another. Tailored solutions help people better apply local knowledge. Such can be true for organizations, too, where—returning to the example of longer working hours—marrying flexible schedules with transparent, outcome-based accountability systems allows people to tailor their work habits to be happier and more productive in their niches. Of course, there might be a context where a more flexible work schedule just won’t work, but context matters. And that is rather the point.

Sustainable, Humane Relationships

The willingness to meet people where they are can come at a cost in the short term, but the long-term benefits are profound. Such an approach not only aids in finding better solutions but also fosters a culture of respect and collaboration.

Meeting people where they are is decidedly not “inclusion,” a la Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI), which means “we become aware of our privileges, or lack thereof, in our interactions,” a definition recently scrubbed from a university website. To obscure a critical social justice agenda, many organizations have dialed the radicalism back to, “Inclusion means a person can be their authentic self in the workplace.”

No.

And not all concerns are equal or valid. It’s just that when leaders start with empathic engagement, people are more willing to listen, cooperate, and even sacrifice for a common mission if they are understood and respected. Such helps leaders build sustainable, mutually beneficial relationships among colleagues and citizens.

The next time you find yourself ready to make a demand or a grand plan, reflect upon whether you’ve taken the time to understand those you’re engaging. Respectful, empathic communication sparks a discovery process. Deeper engagement will help leaders adopt more flexible protocols and tailored solutions.

Max Borders is a senior advisor to The Advocates. He writes at Underthrow.