BREED LOVE: What the Country’s First Female Self-Made Millionaire Taught Us About Free Markets

This article was featured in our weekly newsletter, the Liberator Online. To receive it in your inbox, sign up here.

“Don’t sit down and wait for the opportunities to come. Get up and make them!” Sarah Breedlove Walker

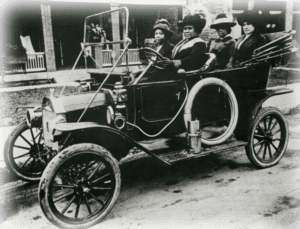

Sarah Breedlove, also known as Madam C. J. Walker, had a tough but incredibly fulfilling life.

The African American entrepreneur, philanthropist, and political activist became one of the wealthiest black women in the country by launching Madame C.J. Walker Manufacturing, a company created to meet her communities’ cosmetic needs.

The African American entrepreneur, philanthropist, and political activist became one of the wealthiest black women in the country by launching Madame C.J. Walker Manufacturing, a company created to meet her communities’ cosmetic needs.

Born to enslaved parents in 1867, Breedlove was the first child in her family to be born as a free woman. As a young woman, Breedlove went through severe financial hardships, but once she moved to Saint Louis, Missouri, she became aware of some of the health difficulties people in her community suffered.

Some of the issues Breedlove saw other black women experiencing included severe dandruff and other scalp ailments associated with skin disorders caused by the lye added to the soap of the era, as well as other socio-economic factors.

Seeing so many women like her suffer from these ailments prompted her to act.

Once Breedlove saw a demand for better cosmetic products designed for different types of skin, she first sought more information on hair care with her brothers, who were barbers. In no time, she became a commission saleswoman for Annie Turnbo Malone, the owner of the Poro Company.

As the time passed, Breedlove used what she learned from her work along with the knowledge she had gathered as a result of her own research, developing her product line.

In 1905, Breedlove moved to Colorado where she and her daughter launched their business. The door-to-door saleswoman would teach other young black women how to style and care for their hair locally until 1910, when Breedlove established her business in Indianapolis, training other women to use “The Walker System,” her own method of grooming that promoted hair growth and scalp conditioning.

For about a decade, Breedlove employed several thousands of black women as sales agents. By 1917, Madame C.J. Walker Manufacturing had employed nearly 20,000 women.

Breedlove took pride in her system, but she also wanted to see others like her flourish.

Instead of just training employees, Breedlove started teaching others about finances and entrepreneurship, empowering an entire generation of black women through the establishment of the National Beauty Culturists and Benevolent Association of Madam C. J. Walker Agents.

During the National Negro Business League (NNBL) annual meeting in 1912, Breedlove celebrated her individuality and self-empowerment by stating:

“I am a woman who came for the cotton fields of the South. From there I was promoted to the washtub. From there, I was promoted to the cook kitchen. And from there, I promoted myself into the business of manufacturing hair goods and preparations. I have built my own factory on my own ground.”

Breedlove was special because she never complained. Instead, she looked around and saw an issue that she could solve. Through markets, she learned to compete by offering a product that met the demands of people in her community. As she grew as a businesswoman, she also gave back, teaching others that hard work and dedication pay off in the end.

Sarah Breedlove Walker may have not always seen her own story as an example of how markets help empower the individual. But this generation of young women could learn a great deal from her. Not just because of her defiance in the face of difficulties, but also because of her vision. Instead of simply demanding attention to her cause, Breedlove made her mark in the world by helping others (while helping herself).

As the F. A. Hayek character says in The Fight of the Century: “Give us a chance so we can discover/The most valuable ways to serve one another.”