The fight is being waged on all fronts, and the most insidious idea employed to break down society is an undefined equalitarianism. […] Such equalitarianism is harmful because it always presents itself as a redress of injustice, whereas in truth it is the very opposite.

Richard Weaver, from Ideas Have Consequences

About ten minutes from my old apartment in Austin, one professor, Daniel Hamermesh, kept an office at The University of Texas.

Hamermesh found his fifteen minutes when he suggested that attractive people have advantages over ugly people, so deserve to be a protected class.

Did he have a point? Should the fruits of good looks be redistributed among the less attractive? Looks (good or bad) are arbitrary, after all.

Here’s Hamermesh writing in The New York Times:

Ugliness could be protected generally in the United States by small extensions of the Americans With Disabilities Act. Ugly people could be allowed to seek help from the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and other agencies in overcoming the effects of discrimination. We could even have affirmative-action programs for the ugly.

Hamermesh’s fifteen minutes was magnified by his appearance on Comedy Central’s The Daily Show. Correspondent Jason Jones had fun discussing “uglo-Americans.”

Jones walked around with Hamermesh on UT’s campus, rating co-eds on a scale of one to five. What was so funny about this segment? A lot. But the funniest thing was that Hamermesh took his idea very seriously: One’s looks, after all, are something you win in the “natural lottery.” You don’t do any work to be cute and sexy. Why do you deserve much of what your cuteness and sexiness yields?

I used to think it was pretty self-evident to think people should be able to take advantage of their unequal natural endowments. I even used the example of looks once to expose wealth redistribution’s absurdity.

“[P]eople use their natural endowments to gain advantages in individual acts of consensual exchange in both dating and trading,” I wrote in 2010.

Such results in natural inequality in the distribution of sex and money. The distribution is such that ugly people normally get dates with other ugly people if they get dates at all. Sexy people get dates with sexier people—and more of them. I think we can agree that it would be wrong to suggest ‘redistribution’ based on any abstractions like the distribution of dates among the sexy and the ugly. So why is this different for other outcomes of consensual exchange?

I guess I was too clever by half.

Leave it to the intellectuals to double down on any absurdities you might expose. The point, though, is not so much to join Comedy Central in poking fun at Professor Hamermesh. He was only a tiny plot point in a pointillist’s painting—one among millions of intellectuals paid to justify taking the earnings of the successful.

It turns out his sexy tax had been a harbinger of absurdities to come.

Perhaps it’s unfair of me to conjure up one of the academic left’s more obscure proposals. But as I’ve written elsewhere, the idea keeps resurfacing that natural attributes are arbitrary, so justice demands violent redress.

We have to wonder why so many intellectuals have such egalitarian authoritarian leanings. But at some point, the justifications differed: Where Hamermesh’s proposal turns on the arbitrariness of natural attributes and seeks to correct for this (redistribute because group x can’t help that they’re born x), social justice fundamentalist ‘scholarship’ agrees that natural attributes are arbitrary, but justifies redistribution despite that fact (redistribute because a group was born x, and group x’s members have been mistreated in the past). In one case, an individual is evaluated according to natural disadvantage. In the other case, groups are evaluated according to historical disadvantage. In both cases, justice is understood as a Cosmic Scoreboard.

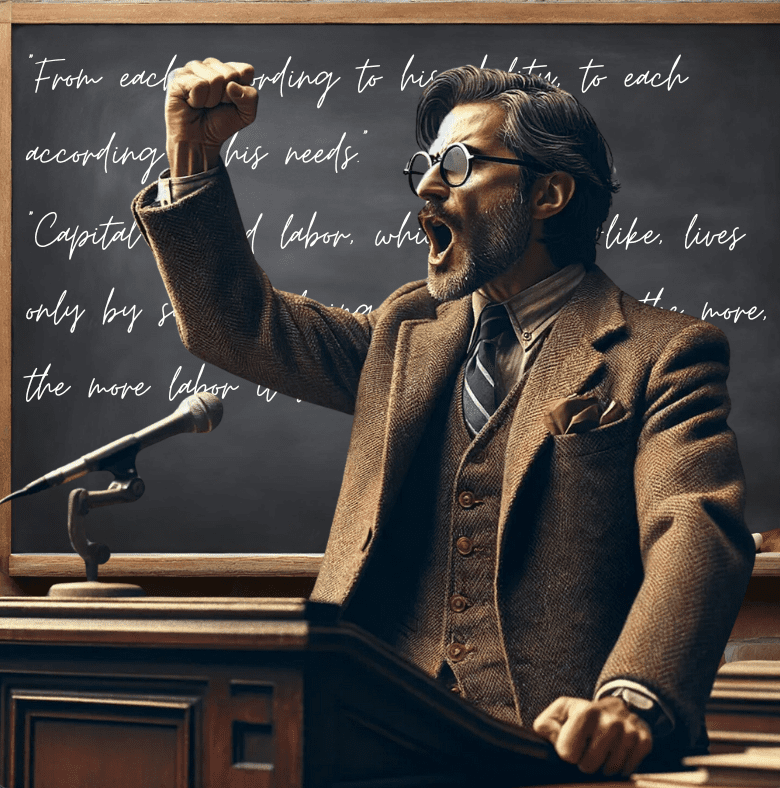

Intellectuals and Redistribution

If academia is, itself, a purgatory of redistributed wealth, it is also a museum of strange ideas about redistribution. Such prompts the question: Why are universities chock full of radical egalitarians? And why do so many intellectuals advocate redistribution?

Remember: It’s not just to argue that you ought to share (compassion); it’s to argue that men with guns should make you share (compulsion). And a lot of really smart people support the idea—so many, in fact, that if you’re reasonably intelligent and you don’t support soaking the rich, you might start to gaze at your navel.

How could such smart people be in the grip of groupthink?

Could people like me who don’t support redistribution be missing something?

Are intelligent people morally enlightened in ways the rest of us are not?

When it comes to such questions, there are a few giants on whose shoulders we can stand. Though they are in the minority, a few top-notch intellectuals have asked similar questions about the connection between academics and egalitarianism.

Their answers are fascinating.

But before exploring those answers, I admit I don’t know that a single explanation will do. I wish I could offer a single, sweeping thesis—such as this one:

A pair of sociologists think they may have an answer: typecasting. Conjure up the classic image of a humanities or social sciences professor, the fields where the imbalance is greatest: tweed jacket, pipe, nerdy, longwinded, secular—and liberal. Even though that may be an outdated stereotype, it influences younger people’s ideas about what they want to be when they grow up.

Any of the following hypotheses, including typecast theory, could be partially correct and work in combination.

Anyway, let’s see what else we can see.

Secondhand Dealers in Ideas

The great F.A. Hayek was one of the most important thinkers to discuss “the intellectuals and socialism”. In his famous 1947 article of the same name, Hayek observed:

In the light of recent history it is somewhat curious that this decisive power of the professional secondhand dealers in ideas should not yet be more generally recognized. The political development of the Western World during the last hundred years furnishes the clearest demonstration. Socialism has never and nowhere been at first a working-class movement. It is by no means an obvious remedy for the obvious evil which the interests of that class will necessarily demand. It is a construction of theorists, deriving from certain tendencies of abstract thought with which for a long time only the intellectuals were familiar; and it required long efforts by the intellectuals before the working classes could be persuaded to adopt it as their program. (Emphases mine.)

When Hayek refers to “recent history,” he no doubt means the National Socialism of Germany, the Stalinism of Russia, Fascism in Italy, the U.S.’s New Deal, and the then-rising Fabian Socialism of postwar Britain—the latter, which Hayek saw firsthand as he wrote from his post at the London School of Economics (LSE).

You see, intellectuals worldwide had been utterly dazzled by all manner of redistribution and planning schemes back then, too. Hayek commented that “intelligent people will tend to overvalue intelligence.” This was not a casual observation for the Austrian economist; this was the intellectuals’ “fatal conceit,” which would lead those boffins to conclude that societies and economies were like machines that could and should be designed, planned, and implemented by intellectual elites. Philosopher kings-in-waiting should organize society.

After the horrors of the early 20th century, Hayek thought a little humility was in order. But the intellectuals ignored Hayek, and their enchantment with redistribution persisted for forty more years.

Then something happened: The Berlin Wall fell. Then the Soviet Union collapsed.

Communist dictatorships in Eastern Europe toppled like dominoes, and the Soviet Union broke apart. This should have proved once and for all that socialist ideals were not sustainable, if they were realizable at all. Reality had finally answered the intellectuals, but their academic paper mills, tenured professorships, and very identities were bound up in all those failed theories.

Authoritarian socialism might have been disproved by history but to accept market capitalism was beyond the pale. Instead of abandoning socialism, they concluded it needed tweaking and rebranding. So, the intellectuals set out to tweak and rebrand for the next twenty years. This would give egalitarianism time to morph and reemerge as something more strange and insidious.

Phrases like “social justice,” “distributive justice,” and “progressivism” found new life. Some of the old socialist intellectuals flocked to the environmental movement, which gave central planning a green veneer. Others sought to develop milder forms of socialism that, unlike communism, would preserve the geese that laid the golden eggs—but take every other egg for the state. Indeed, many held up Scandinavian models of democratic socialism, which tossed central economic planning but preserved redistribution.

But even those Swedish geese got worn out in the 1970s and 1980s.

The academics moved their trenches again and regrouped around ideas that tempered, hid, or ignored the brutality or unworkability of various socialisms. In their place, they would erect massive welfare states fueled by debt. European welfare statism would become the clerisy’s religion.

It still is. Sort of.

But critical social justice came along and colonized the universities, so stranger contrivances distracted new generations from the so-called class struggles proffered by the Old Left.

So now, redistribution is not just about income but also positions and offices. And dates.

Welcome to the wacky world of diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Max Borders is a senior advisor to The Advocates, you can read more from him at Underthrow.